Comptroller Study Shows Difficulty of Predicting Future Tax Revenue

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2014/09/03/ComptrollerLeadArt-Tax.jpg)

As Texas lawmakers convene in January for the next legislative session, their chief task will be to write a two-year budget. And the state's next comptroller will be charged with estimating how much revenue lawmakers can expect to work with.

The responsibility has become a political minefield, particularly after Comptroller Susan Combs’ estimate ahead of the 2011 session drew criticism for underestimating tax revenue by several billion dollars. Combs’ office recently researched the accuracy of revenue estimates going back 40 years and found that, by one measure, other comptrollers’ estimates have landed farther from the actual number.

Since 1942, the Texas Constitution has required that the comptroller produce a Biennial Revenue Estimate to provide lawmakers a guide of how much money they have available for their next budget. Texas is one of only four states that meets every two years instead of annually. In the past, critics have argued that the state should meet every year, citing the difficulty of properly anticipating the state's needs so far in advance.

Chief Revenue Estimator John Heleman, who led the study, analyzed the estimates of tax collections in the Certifiable Revenue Estimate, which is the updated forecast the comptroller provides after each legislative session. Heleman said he focused on that figure rather than the one the comptroller provides before the legislative session because the CRE factors in changes made to tax laws made during that session, some of which can have dramatic impacts on revenue.

Why go back only 40 years? Before that, Heleman found that the state budget was structured differently, making it difficult to make an apples-to-apples comparison between those older revenue estimates and more recent ones, agency spokesman Chris Bryan said.

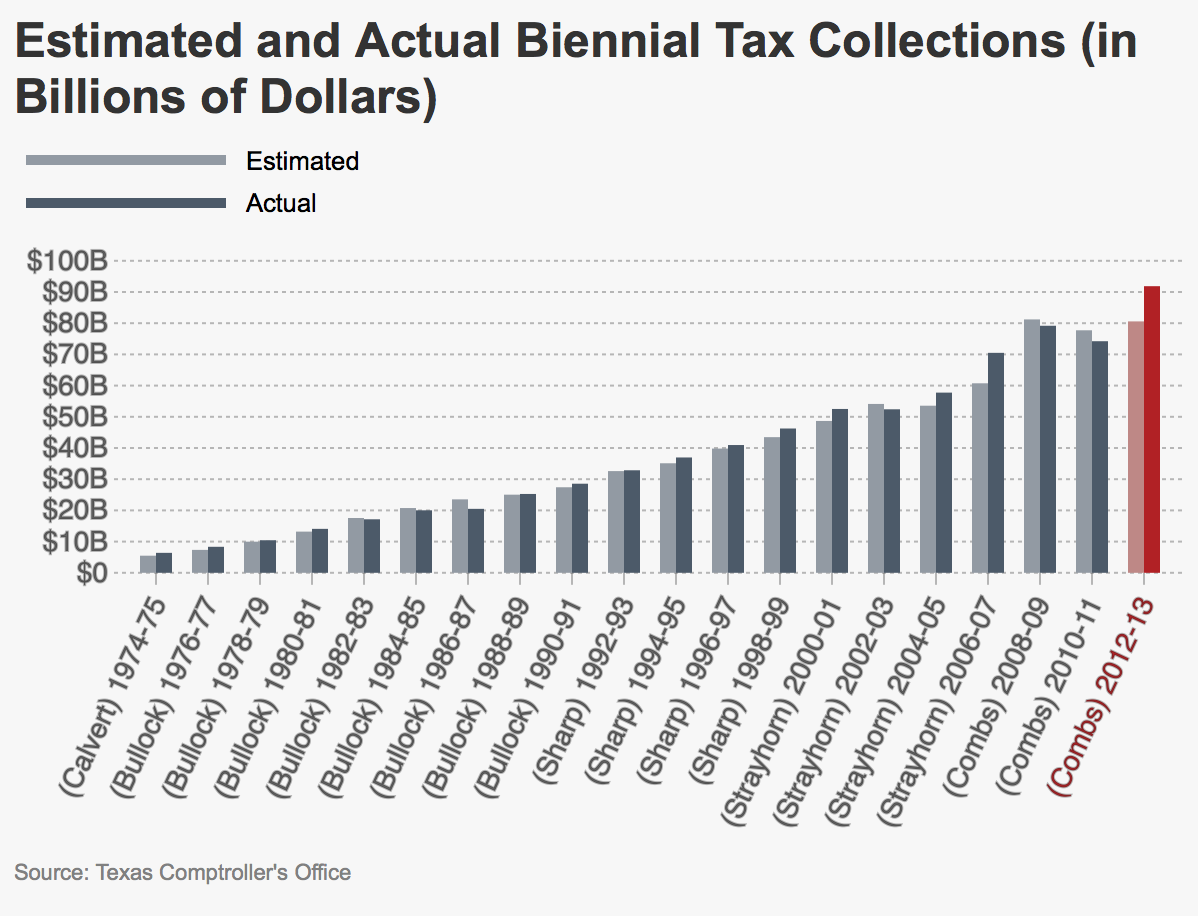

The study found that Combs’ 2011 estimate, which forecasted how much revenue the state would collect during the 2012-13 biennium, was off by $11.3 billion, a 14 percent miss. No other estimate since 1974 has been as off on a dollar basis.

This graph shows the estimated and actual tax collections for each biennium and includes the corresponding comptroller who made the revenue estimates for that biennium.

However, two older estimates were off by more on a percentage basis. In 1973, Comptroller Robert Calvert’s estimate for the 1974-75 biennium underestimated revenue by nearly $1 billion, a 16.7 percent miss of state revenue of just over $6 billion. In 2006, Comptroller Carole Keeton Strayhorn’s revenue estimate for the 2006-07 fiscal year fell short by $9.8 billion, a 16.1 percent miss.

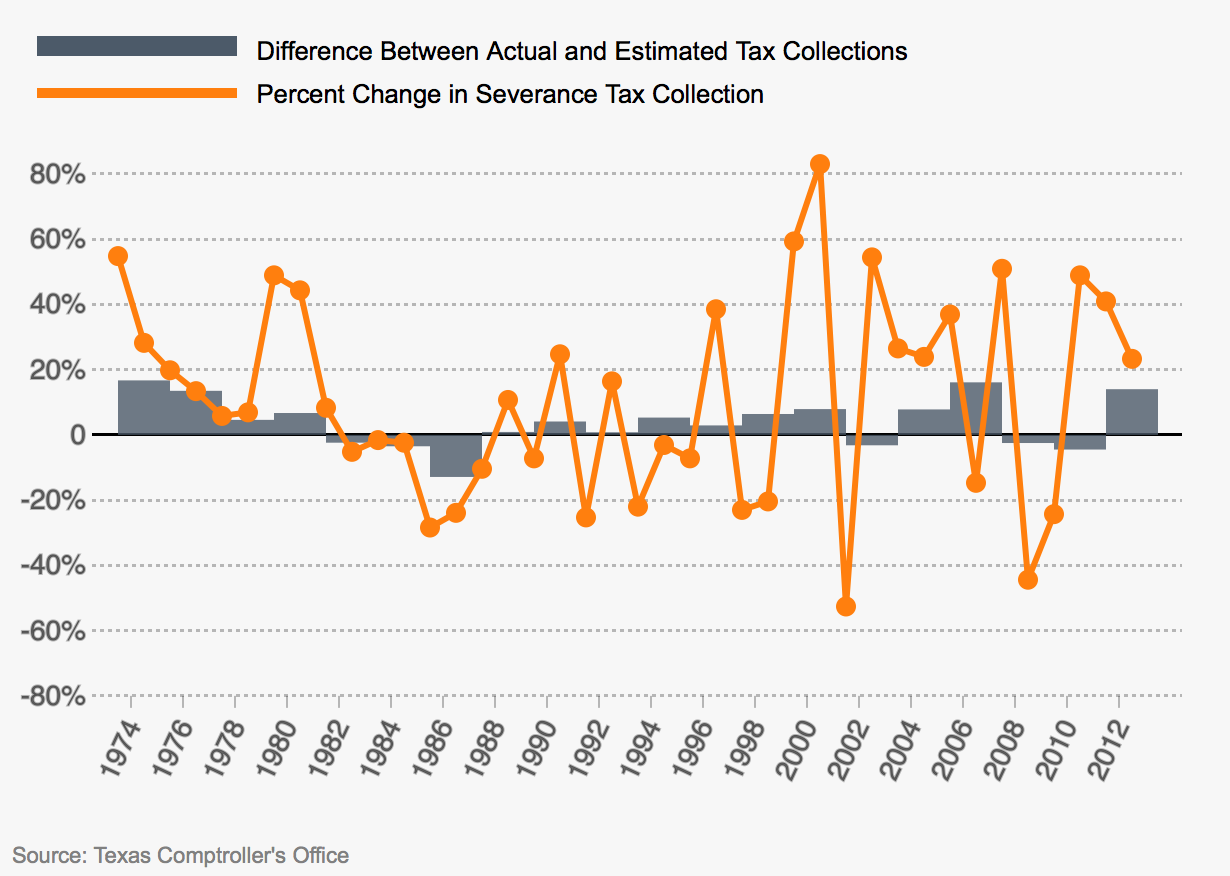

This graph shows the change in estimated and actual tax collections for each biennium and includes the corresponding comptroller who made the revenue estimates for that biennium.

Lawmakers cut more than $5 billion from public education in 2011, after Combs forecasted a large shortfall. Prior to the next session in 2013, Combs reported an $8.8 billion surplus in state coffers. Lawmakers involved in the budget-writing process have since said the Legislature would not have cut as deeply from education in 2011 if the comptroller’s estimate had been more on target.

Combs has defended her 2011 estimate, noting that it was not clear at the time if Texas was fully out of the recession. She also cited the energy boom at the time, saying it was tricky to gauge given that industry’s volatility.

Heleman found that shifts in the energy industry have frequently collided with particularly wide revenue estimates.

“In the past 40 years, almost every instance of overestimated tax collections occurred as a result of recession and/or precipitous declines in energy prices,” the study reads. “Underestimates were associated almost exclusively with soaring energy prices, new technologies in the oil and natural gas industry, and/or boom periods in the economy featuring rapid employment growth and expansion in the housing market.”

Use these graphs to compare the accuracy of revenue estimates over time to changes in nonfarm employment and changes in collections of the severance tax, which is placed on oil and gas production.

Mike Collier, the 2014 Democratic nominee for comptroller, has accused Combs of paving the way for the firing of thousands of state teachers with her 2011 estimate. He has made improving the comptroller’s accuracy on revenue estimates a key plank of his campaign against Republican Glenn Hegar.

“I have the mind to do them quarterly versus every other year,” Collier said. “My point is if we chronically underestimate the revenues, then we will then chronically under-invest in the areas that we know we must.”

Hegar has said that he wants to “completely re-evaluate how we do the revenue estimating in that division.” He has also defended Combs’ 2011 estimate as a difficult task given the volatility in the economy, particularly the energy sector, at the time.

Information about the authors

Contributors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/batheja-aman_G6q1v70.jpg)