In Texas Drilling Country, Oil Plunge Means Too Many Rooms at the Inn

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2016/04/11/IMG_0686.jpg)

COTULLA — Sitting behind the front desk of the barracks-style motel they own on this South Texas town's Main Street, John and Carolyn Nelson had plenty of time to chat. As a recent weekday afternoon turned to evening, no guests had checked in.

“We’re completely empty right now,” said John, 68, pushing aside the remnants of a dinner featuring orange sauce as a TV Land rerun flickered on a television.

More than two dozen vacant rooms, little work for their bare-bones staff — the couple said they have grown used to this in recent months, staying afloat almost solely thanks to a dry-cleaning business on the same property. But life wasn’t always this slow in this town, about 90 miles southwest of San Antonio. Far from it.

From 2009 through most of 2014, Cotulla rumbled amid drillers’ mad dash to the oil-rich Eagle Ford Shale. Business boomed for anyone who offered beds to the thousands of workers coming to town. Competitors sprouted like weeds after the rain, sometimes charging sky-high rates for a small town.

The town, population roughly 4,000, built 20 new hotels. Before the boom? It had just four, including the Nelsons’ 60-year old Cotulla Motel.

Now a dramatic plunge in oil prices has meant crashing revenues and rising angst for the outsized hospitality industry, continuing a time-honored tradition in Texas drilling communities.

West Texas communities, which have boomed and busted throughout their oil-fueled history, have seen this before. In the 1980s, hotel revenues leaped and dipped like a ballet dancer. But for Cotulla and other towns new to crude dependence, this is their first taste of that tradition.

“That’s what’s happened before, and what’s happening now," said Todd Walker, senior vice president of San Antonio-based Source Strategies, a hotel industry consultant. “They don’t have enough rooms when it’s booming. Then they build a bunch of rooms, and they’ve got too many rooms.”

Though hardly the only sign of trouble in Cotulla, the empty hotel parking lots here are providing some of the most prominent symbols of the economic whiplash volatile oil prices have inflicted on oil towns scattered not only across Texas but also in Oklahoma, Louisiana, North Dakota and beyond.

After surging each year since 2010 — at times more than double the growth across the state — hotel revenues in Texas drilling counties fell of a cliff in 2015, according to a Texas Tribune analysis of data provided by Source Strategies.

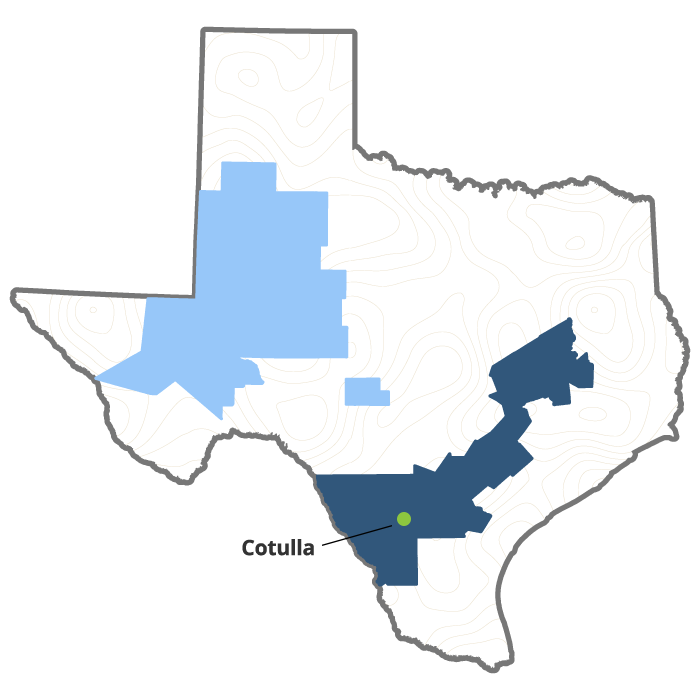

In the 26 Eagle Ford counties in South Texas (as defined by the Texas Railroad Commission) revenues dropped 19 percent last year after nearly doubling over the previous four years. In West Texas’ Permian Basin, revenues tumbled 16 percent in 2015 after rising even faster since 2010.

Eagle Ford shale counties

Permain Basin shale counties

The trends were far more pronounced in the state’s top oil-producing communities: In La Salle County — home to Cotulla — hotel revenues fell almost 41 percent in 2015. Gonzales, a few counties to the southeast, saw a nearly identical plunge. Statewide, revenues grew by more than 3 percent over the year.

And the bleeding appears to have worsened in 2016. Though per-barrel West Texas crude prices have inched up to around $40 in recent weeks, they’ve stayed stubbornly low throughout the year — a far cry from the heady $100 days of summer 2014. And Texas oil sector layoffs, now in the tens of thousands, continue to climb.

So what will become of all those hotels?

Developers may convert some to other uses, Walker suggested, but other developers are likely to walk away, leaving locals to ponder how to fill the buildings.

If oil prices don’t recover soon, Cotulla may face a heavy dose of head scratching. One hotel has already closed: the earth-toned Malana, whose four stories rising off Interstate 35 sought to offer rare luxury to dusty travelers. The project hit various snags throughout its development, several people who followed it say, pushing its opening into the downturn — too late to recoup the costs.

If other closings follow, La Salle County Judge Joel Rodriguez Jr. worries that the buildings could turn into hazards, eating up the resources of his busy fire crew. With the help of oil money, the county recently beefed up its emergency response capabilities, but the department still can’t afford a ladder truck that would reach the top of the taller hotels.

“I don’t know if there’s anything I could do or the city could do,” he said. “It’s done. The permits are there."

But Cotulla City Administrator Larry Douvalina, whose tenure has spanned the boom, is staying relentlessly positive, calling the town’s reputation as the “Hotel Capital” of the Eagle Ford an “asset” that could reel in other businesses and potentially withstand the downturn.

He and some business leaders brag about two companies’ plans to build a $240 million natural gas plant nearby. And they speak of setting up a “free trade zone” — an area where international companies could handle, manufacture and re-export goods without U.S. customs officials intervening. Some Mexican companies may come, they suggest, trying to escape congestion in Laredo, the border town about 70 miles southwest of here.

“We continue to see activity that most other cities wouldn’t see,” Douvalina said.

In the first three months of 2016, the city’s total sales tax collections dropped 32 percent compared to 2014 levels. Anticipating that drop, the town cut spending this year by about 40 percent. But far more money is coming in now than it did before the boom, when the town was struggling to survive, Douvalina and other optimists say, and it has allowed the city to pay off debt.

“It’s just a waiting game. And I can tell you, it’s going to come back,” said Brenda Wright, president of the local chamber of commerce. “And it will come back with a vengeance, like the very beginning.”

Still, some within the hotel industry see a bleaker future — an oil recovery too slow to save businesses in a community where, save for some out-of-town hunters, few people have reason to visit. (Many folks drive to either San Antonio or Laredo for excitement, several locals said).

“It’s a small town. Nothing’s going on. There’s only oil,” said Stephanie Patel, managing partner at the La Quinta Inn and Suites, which opened in October 2013 and appears to be one of the community’s busier hotels — a relative term. “I like Cotulla. I like what it has. It’s not for everybody.”

A binder greeting La Quinta guests lists just five “points of interest” in the area: a library, museum, western wear store, post office and the chamber of commerce.

“If it stays like this, it’s, like, kind of scary,” Patel said. “Everybody’s trying to survive right now.”

John Nelson echoes that assessment of his hometown. “Why would someone want to come to Cotulla? There’s nothing to do,” he said, bristling at his newfound reality: While the hotels here still pour more cash into city coffers than they did before the boom, the fierce competition means he gets just a sliver of the pie.

“It’s never going to come back like it was. It never will,” he said. “Everybody got so damn greedy.”

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Jim_1.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Lauren-Flannery_new.jpg)